Da: Davide Faccioli (a cura di), 100 al 2000: il secolo della Fotoarte, Edizioni Photology, Milano 2000, pagg. 194-195.

Gelatin silver print

Gelatin silver print

46 x 38 cm

Private Collection, Bologna

Si è detto che ogni opera a vocazione artistica è una preghiera per ottenere una nuova immagine. E che talvolta la preghiera è esaudita.

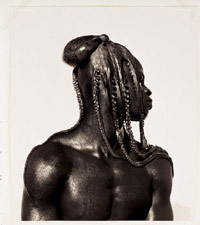

Non so se è il caso di Djimon con polipo di Herb Ritts.

L’insistito estetismo – formato ritratto di profilo, torso scultoreo, esotismo senza ironia – fa pensare piuttosto all’album decorativo, se non al coffee table book.

È in ogni caso questo il mio effetto studium, risultato dell’osservazione assidua, direbbe Roland Barthes. Ma c’è nella fotografia qualcosa che punge, che tocca un senso e presentimento.

È l’occhio del polipo, alla sommità del capo di Djimon. E il tentacolo che seguendo esattamente la nuca e la spalla, segna e promette una incipiente metamorfosi.

L’effetto è ottenuto scontornando l’immagine e isolandola in un fondo intemporale e impersonale. E col trattamento della luce: non quella che evidenzia l’atletismo dell’uomo e la mollezza del polpo, ma il lustro, cioè il riverbero cutaneo dell’uno e dell’altro. Luce della sostanza, non della forma.

Il punctum quindi non è l’acconciatura barbarica di Djimon, ma il suo farsi polipo, il suo divenire animale, agglutinato nella consistenza colloidale della stessa carne.

Quando l’occhio dell’octopus, fisso su di noi tra i tentacoli, ci avverte forse che l’opposizione mitica post-moderna non è quella tra Apollo e Dionisio, ma tra Proteo e Medusa. Non tra la composta bellezza e la frenesia, ma tra le mutazioni e gli spaventi.

L’icona “polpodjimon” può diventare allora l’enunciato minimo di un mito ecologico che la giustifica e di un cerimoniale da inventare.

Un minuscolo mitogramma africano a cui le tecnologie mediatiche restituiscono l’aura? Immagine turistica kitsch o creolizzazione visuale? Difficile dirlo. Ma come ritrarre oggi una cultura altra?

Per Williams Carlos Williams “the pure product of culture are all gone crazy”. Vista la nostra immagine tradurremmo “i prodotti puri di una cultura sono tutti via di testa”.

They say that each work which attempts to become an artistic statement is a prayer for a new image. Sometimes the prayer is answered.

I don’t know if this is true in the case of “Djimon with Octopus” by Herb Ritts.

The insistence on the aesthetic, the portrait in profile, the sculpted look of the torso, the exotic without irony, they all make me think of a coffee table book.

In any case, this is what my careful study, or what Roland Barthes called “studium”, came up with. But there is something else in the photograph, something that has a sting to it, touches a nerve, a presentiment.

It’s the octopus’ eye, on top of Djimon’s head, and the tentacle that follows exactly along the nape of his neck and shoulder which indicates that some weird change is going on.

The photographic effect is achieved by treating the image as a silhouette and isolating it in time and impersonal space.

That and the treatment of the light: not the one which shows how athletic the man is or how soft the octopus is, but the way the shine reverberates from the skin of one to the other. The light shows the substance, not the shape.

So, the point is not Djimon’s barbaric headgear, but the fact he’s changing into an octopus, a sea animal, with gelatinous, slimy flesh.

When the octopus’s eye, in the middle of the tentacles meets ours, it could be warning us that the mythological opposites in post-modernism lie not with Apollo and Dyonisius but instead with Proteus and Medusa.

Not with composed beauty and frenzy but mutation and horror.

The octopus-Djimon icon could yet become the symbol of an ecological myth which requires it and of a ritual ceremony yet to be invented.

A tiny African mythogram that media technology has given back its aura?

Tourist kitch or visual creolization? Difficult to say. But how does one draw the portrait of “the other” today?

For Williams Carlos Williams “The pure products of culture have all gone crazy”.